Trigger Warning: This story contains mention of suicidal thoughts that may be triggering to some.

I hope that by sharing my journey, you’ll walk away more aware of how adoption shapes identity and how LGBTQ youth grow through layers of love, struggle, and discovery. My wish is that you’ll feel inspired to “adopt” someone into your heart — with empathy, acceptance, and patience. Life can be heavy, but with conviction, faith, and even a simple smile, we truly can overcome.

From the outside, my story might appear filled with blessings, laughter, and love. Yet behind the scenes lived quieter moments that completed the picture — fear, confusion, and a deep sense of loneliness that often felt impossible to explain.

Who am I? I am a gay Filipino cisgender man adopted into a white family and raised in a predominantly white community where most families shared biological ties. I was born in Davao City to a young unmarried woman who, overwhelmed by circumstance, turned me over to the Ministry of Social Services and Development. I spent my earliest days at the Reception Center for Children.

My birth mother, Evelyn Casilac, was only 23 when I arrived. She was one of eleven children, petite with curly black hair and a gentle face. During university, she fell in love with Rodrigo, a tailor from downtown Digos. Their relationship had to be kept secret — and when she became pregnant, he disappeared, denying responsibility and vanishing from her life.

Left heartbroken and terrified, Evelyn faced her pregnancy alone. Shame, fear, and despair grew so heavy she attempted suicide, risking both her life and mine. She worried about returning home unmarried and pregnant, afraid of rejection from her parents and siblings. Seeking safety, she turned to the Paglaum Foundation Inc. while six months along. Two months later, on August 2, 1986, I was born and named Roilan Abendan Casilac.

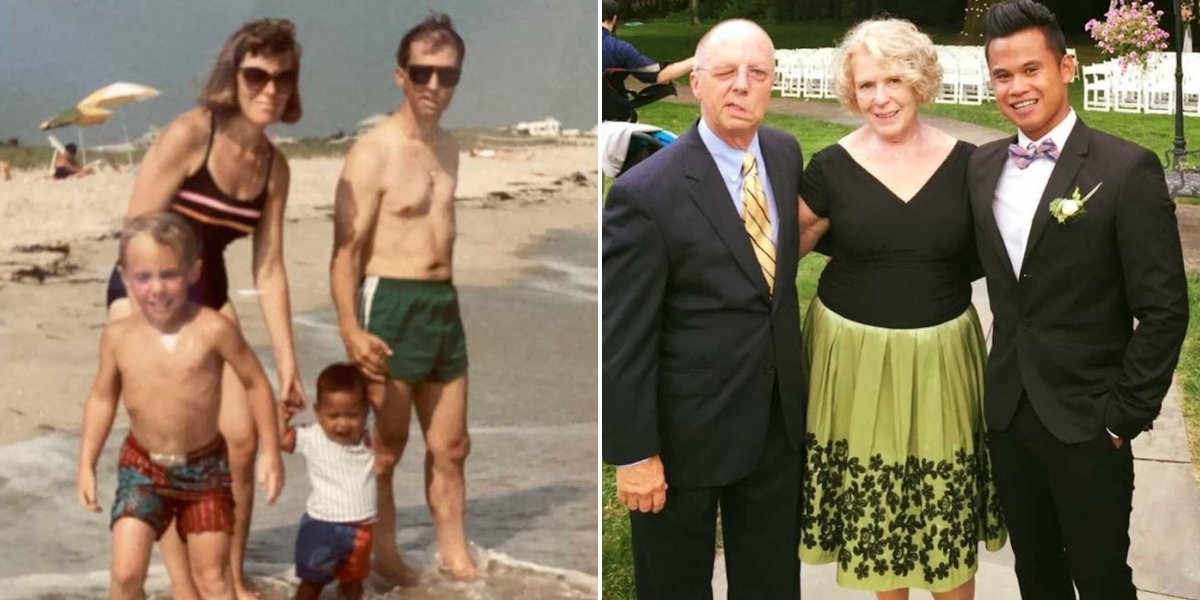

Meanwhile, across the world in Brookfield, Connecticut, Mary Ellen and Bob Wheelock were working with the International Alliance for Children to welcome another child. After a difficult pregnancy with their son Jonathan, they dreamed of expanding their family through adoption — and hoped their six-year-old would soon have a sibling.

Twice they were matched with Filipino infants, and twice the paperwork disappeared. Then came my file. On June 19, 1987, I boarded my first international flight with Dr. Manlongat from the Manila IAC office and landed in the arms of the Wheelocks, who greeted me with tears, love, and total openness. They named me Andrew Roilan Wheelock, honoring my heritage by keeping my first name as my middle name — a choice I still carry with gratitude.

My childhood was full of motion. My parents made sure I stayed connected to Filipino and adoption communities whenever possible. I was baptized at St. Joseph’s Church, where one of the priests, Fr. Paul, was Filipino. My mom even befriended someone who was half-Filipino — and decades later, that friendship remains.

But alongside the joy were moments that stung. My mother once recalled pushing my stroller when a stranger paused, looked at me, then asked her bluntly, “Why would you do that?” For the first time, my parents realized not everyone would see adoption as an act of love.

As I got older, the differences became clearer. My classmates often resembled their parents; I did not. Though I understood adoption well, I sometimes wondered what it felt like to physically “match” your family. I was outgoing and cheerful, yet tiny interactions — cashiers questioning whether I belonged with my parents — quietly reminded me that I was viewed as an outsider. To compensate, I’d intentionally call out “Mommy” or “Daddy,” trying to reassure both strangers and myself.

Sports and school filled my days — soccer, swimming, gymnastics, baseball, tennis. I excelled athletically and bonded with my dad over soccer. In Home Economics, sewing came naturally to me, echoing the craft of the biological father I’d never known.

Jonathan, six years older and biologically related to my parents, had his own path. Creative and sensitive, he struggled in school at times while I thrived socially and athletically. Over the years, the gap between us widened, and for a time I felt like I barely had a brother at all — each of us fighting different battles in silence.

Behind my smiling exterior, I carried questions that grew heavier with time. At nine, I began experiencing same-sex attraction. Raised Roman Catholic, it terrified me. I prayed intensely, desperate for answers, and feared one possibility more than anything else: If my parents found out, would they send me back?

I buried those feelings and threw myself into activities like music and theater, which became a place where I could breathe. Then one Sunday, I heard a priest say, “God created each of us for a special purpose. He doesn’t make mistakes.” At thirteen, those words changed everything. Quietly, I accepted myself — I was gay.

Coming out was the next step.

At fourteen, during a car ride with my mother, I told her. It was terrifying — either keep hiding or risk everything. My parents were shocked, imagining the grandchildren they might never see. They urged me not to tell anyone until after high school, worried I’d face the same brutal bullying Jonathan did. But I eventually confided in friends anyway — and they wrapped me in encouragement and love.

Yes, I was teased. Yes, I experienced suicidal thoughts. But I refused to surrender. After surviving adoption, identity struggles, and isolation, I realized taking my life meant letting cruelty win — and I chose not to.

Acceptance came gradually for my parents. My father, deeply Catholic, believed my life would only bring hardship. During one long-term relationship, he and I barely spoke for nearly two years. Only later — when he saw me loved, safe, and thriving — did he soften and begin to truly see me. My mother, though cautious, always rooted for my happiness.

Life taught me early that we are layered beings. I learned to hide pain behind smiles and still wrestle with belonging. But I’m discovering something freeing: I don’t have to fit in. I simply have to exist — fully and honestly — as a gay Filipino cisgender man adopted into a white family.

To adoptive parents and those considering adoption: lead with love. Tell your children their story often. Create safe spaces for conversations about difference, and never force them before they’re ready. Offer windows into their cultural roots — but understand some of us need time before we look through them.

We may not always feel like we belong everywhere, but we’re never alone. Through sharing my journey, I’ve connected with other adoptees — including LGBTQ adoptees — whose stories echo mine. Together, we are building community, healing pieces of our past, and reminding one another that there is strength in being seen.

And that is where hope lives.