On October 6, the year I turned one, a gift was due to arrive three days later. Little did I know, I wouldn’t receive it until thirty years later. That gift was my husband—a fellow Libran, someone whose heart and mind mirrored mine in ways I could never have imagined. When we first met in person, it was a small but uncanny coincidence: we both drove Buick LeSabres and owned Toshiba laptops. Even funnier, he had grown up as best friends with one of my closest cousins. I had only known of him by name and seen him once in passing. Later, I discovered he had endured a mental breakdown almost identical to my own. My cousin had warned him, saying, “She’s kind of weird.” But this man, my twin in soul and spirit, told me he could find nothing strange about me.

He is the only person who has called me beautiful every single day since we met. He loves me unconditionally, never judging me or making me feel like an outsider. He is the most genuine soul I have ever known—perfect, in every sense. Meeting him felt like serendipity, and I prayed to the stars he would be mine.

When most people hear “OCD,” they think of cleanliness or neatness and casually say, “I’m so OCD!” But OCD is not just a quirk; it’s a neurological condition that brings relentless emotional turmoil. It manifests as intrusive thoughts—images or ideas that appear unbidden, often disturbing, and impossible to ignore. It’s similar to hearing nails on a chalkboard or the sound of someone cracking their knuckles—painful, jarring, and involuntary. Everyone has intrusive thoughts occasionally, but for someone with OCD, these thoughts repeat over and over, tethered to worry, doubt, and guilt. They play like a broken record in your mind. There was no humor, no punchline, the day I was first labeled “so OCD.”

“What are you thinking right now?” asked the clinician in the hospital room. “I’m thinking, I want to kill you,” I replied honestly. She didn’t understand, and immediately, I was committed to the behavioral ward. No one seemed to comprehend that these were intrusive thoughts—not desires, not plans, just images my mind had forcibly shown me. Even years later, when my nurse-aunt asked if the clinician had made me angry, I had to explain gently: “No. I did not want to hurt her. These were thoughts, images, intrusions—my mind was torturing me.”

Trying to explain OCD to someone who has never experienced it is like trying to describe a broken record only you can hear. People assume trauma, sexual assault, or attention-seeking behavior, never realizing that someone with OCD is in constant, silent battle with their own mind. I kept washing my hands until they bled, repeating prayers and phrases until I felt “things were right,” turning my head back and forth, checking, rechecking, as if my body could absolve my thoughts. All outward behavior, all to fight something invisible.

At sixteen, during my sophomore year, I was diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, accompanied by severe depression and psychosis. I’ve kept my medical records for years—illegible scribbles, small paper cups of Zoloft handed over in the school-room-turned-hospital ward, a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I was homeschooled for the remainder of the year after a relapse and underwent outpatient therapy. Therapists and counselors tried to help me socialize, taking me swimming, bowling, and even to the bank—but none of it was the scientifically supported Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which I would later learn is the gold standard. My intrusive thought, “I want to kill you,” continued to haunt me whenever I faced another person, even as I prayed and tried desperately to regain control.

I learned to privatize my OCD over the years, hiding the chaos inside. It began as early as age six or seven, gradually building until the “Big Thought” hit me at ten—an image so bizarre and terrifying that I had no reason for it. Intrusive thoughts, by nature, are random, unpremeditated. I was loved and protected, yet my mind betrayed me. The disorder ran in my family, though older generations never acknowledged it. My husband, too, experienced his own intrusive thoughts and panic attacks, yet he remained my mirror, my anchor, my twin. Together, we navigated the unseen storm of our minds.

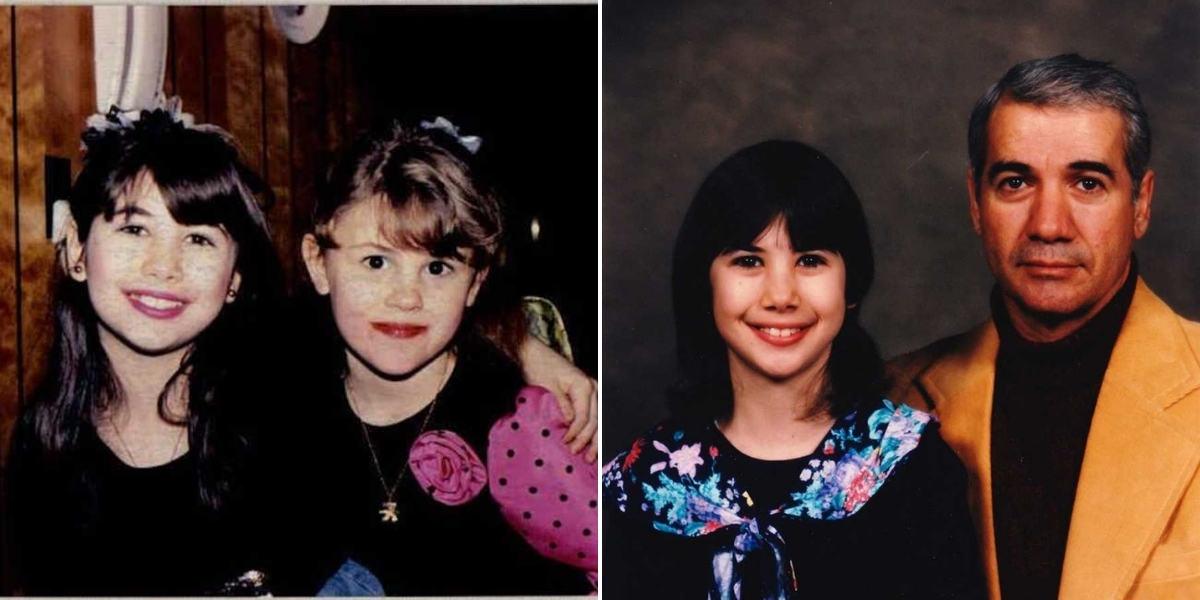

There were moments of unbearable anguish. In high school, I would break down in hallways, make teachers cry with my distress, and come home to my father trying to soothe me while I wandered the living room, trying to “take back” the intrusive thoughts, pressing my fists into my aching belly. My mother had already passed, and the thought of wishing her dead terrified me. I could not reconcile being a good girl with the images in my mind.

Over time, therapy, medication, and shared understanding with my husband helped. He can now sleep beside me without panic attacks, and I can manage my tics and intrusive thoughts more effectively. We support each other—his music, my writing—and take life one day at a time. OCD is real, invisible, and persistent, but it does not define us. Prayer comforts us, treatment stabilizes us, and love sustains us. Intrusive thoughts are like a pink elephant in the room: you can’t force them away, but you can learn not to fear them.

Our journey has been one of struggle and resilience. OCD evolves, but so do we. No demon causes it, no sin prolongs it. We live with it, we work through it, and we love each other despite it. Mental illness is real, and support is real. You are not broken, you are not bad, and help exists. Faith, therapy, and love—they are all part of the path forward. God bless.